How should you shift your typical integration strategy, process and timing when your company acquires a business that is substantially different than your core business?

That discussion was what prompted one of those unexpected moments that I wish I could rewind and record for posterity. We were less than halfway through an executive readout session on the integration strategy framework for a substantially different new acquisition with an experienced large corporate acquirer. With an astonished expletive not fit for print, the CEO exclaimed, “What you just said explains why our prior acquisitions have consistently destroyed so much value.”

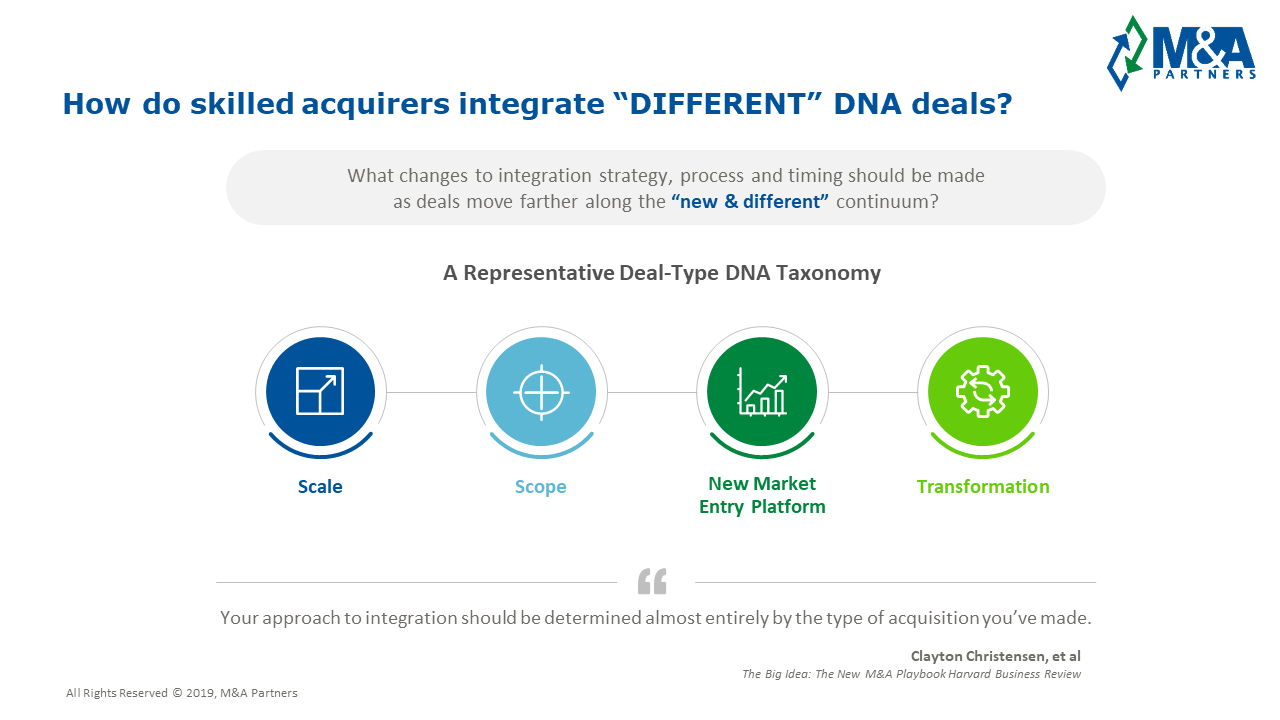

We were talking about what we like to call deal-type DNA and how each specific deal-type heavily influences what, when and how to integrate that specific business in order to maximize value creation and minimize potential value erosion. Unfortunately, this CEO’s eureka moment came a bit too late for last year’s acquisition but established a strategic pivot point on how the organization had routinely approached integration with a one-size-fits-all consolidation mindset.

First, what exactly do we mean by “new and different?” Sometimes called platform deals, the intent is to acquire a mature business and quickly build on the acquired platform, using it as a springboard for rapid growth in that area of strength. In our view, however, the best strategies and best practices for integrating “new and different” should go beyond the traditional definition of a platform company per se, since the same approach and principles are likely to be just as important when you are acquiring a substantially different technology, product line, process, global region or capability.

Based on this broader definition of platform deals (Platforms) let’s more clearly set out examples of what these might include or not. Platforms are not just bringing more revenues or customers to scale a Buyer’s existing core business, service line or solutions. Likewise, it’s not just a product tuck-in that fits neatly into an existing product family, division or unit as a great “gap-fill” or service line extension. They are not mere variations on a theme, but directly orthogonal to what you are, what you do or where you operate today. A Platform is a leap-frog strategy, a brand-new or substantially different foothold or battlefront that you fully intend to preserve, leverage and grow along that new vector. By definition, a Platform entails something substantially new or different that the Buyer has never operated before – at least not at scale and market prominence. For example:

- A product line, technology or customer segment

- A county, region, regulatory or compliance environment

- A business model, operating model or service platform

- A core process, skill set, talent base or culture

We’ve found it helpful over the years to talk a lot about deal-type DNA with any integration leader not already well versed in Corporate Development. In our view, deal-type DNA refers to the nature of the company, capabilities or assets being acquired relative to the Buyer’s company, capabilities and assets; and to the underlying deal-thesis for the acquisition. Generally speaking, deal-type DNA helps executives and integrators define and more effectively articulate answers to two fundamentally important integration strategy questions: “What are we buying?” and “Why are we buying it?” Without this essential context behind the myriad macro and micro integration decisions, acquirers will invariably execute their standard functional integration checklist straight into the abyss of unintended value destruction, just like the aforementioned CEO realized.

For M&A Partners' clients or M&A Leadership Council workshop alumni, you’ll quickly remember the inset illustration, “How do skilled acquirers integrate "Different" DNA deals?”

This representative deal-type taxonomy broadly defines common deal categories, including those mentioned below. A couple of quick caveats apply. This is high level, and there are several similar common terms or categories describing similar concepts. Also, most deals are complex and don’t fit neatly into any one of the deal-type categories alone, but there’s always a primary deal-type and one or more valid secondary considerations.

- Scale deals. The core purpose of this deal-type is about getting bigger in existing core businesses or domains common to both Buyer and Seller. Consolidation, cost-take out and eliminating a major competitor are key objectives.

- Scope deals. The core purpose of this deal-type is about getting broader by buying products/services, brands, capabilities or geographies that extend or “gap-fill” the Buyer’s product or service suite, faster or with better, more established products or technologies than the Buyer could reasonably develop on its own. Key objectives often include product innovation; cross-sales; and accelerating the Seller’s products/services through the Buyer’s customer base, channels or go-to-market capabilities.

- Different DNA deals. Typically, the acquisition target is an intact, mature entity, division or global region, albeit not yet fully at scale. Contrasting with the above, new Platform deals are like an initial strategic beachhead. The Buyer’s intent is to launch its entry into some new and different segment, technology or geography from the Target’s Platform. Key objectives include preserving and leveraging the Platform’s “secret sauce”; investing to grow the platform business; continuing or even adopting essential operating model elements of the platform where needed; and corporate governance that balances alignment to the Buyer’s systems, processes, policies, etc., with an appropriate degree of continued independence for the Platform.

Skilled acquirers who routinely buy a variety of deal-types share a common experience: they’ve completely blown up one or two new Platform or fully transformative deals before learning to adapt their integration strategy, governance and process mechanics as they move farther and farther along the “new and different” continuum. You just can’t integrate a Platform acquisition the same way you integrate a typical bolt-on, tuck-in, scope or scale deal. If you run that play, you’ll be no different than that CEO who realized far too late that integrations of Platform deals don’t fare well if run on auto-pilot.

In our work with skilled acquirers over the years, M&A Partners has researched, validated and applied several strategies and core guiding principles proven to help integrate Platform acquisitions. While not fully exhaustive, these principles have been successfully applied in industries as diverse as software and technology; industrial manufacturing; financial services; and health care. Caveats abound, and these strategies must be carefully adapted to your specific situation, but given that, we know they can be helpful when tackling your next Platform deal.

Six Essential Strategies for Integrating Platform Acquisitions

- Clearly understand and focus all integration decisions and actions on preserving and leveraging the target’s value drivers. Amazon’s 2017 acquisition of grocery retailer Whole Foods for $13.7 billion provides a great example of preserving and leveraging the Platform’s value drivers. A clear Platform acquisition with many highly synergistic growth levers, Amazon saw Whole Food’s affluent customer base and highly desirable physical storefront locations as a unique and symbiotic opportunity to drive its online grocery business with local distribution that would be nearly impossible to otherwise establish. In addition, combining their respective and highly passionate customer bases enabled Amazon to immediately launch an entire series of enormous new cross-sell and cross-promotion opportunities on Day 1. Notable among these customer focused value-drivers were special discounts and cash-back offers for Prime members; Amazon product displays and point-of-purchase sales of popular items in Whole Foods stores; and perhaps most importantly, a significant price reduction on upwards of 1,000 core products and SKUs made possible by more efficiently leveraging Amazon’s superior data, AI and supply chain capabilities.

- Retain the Platform’s organization and operating model for a longer period of time than for traditional acquisitions. As one of its first forays into digital online marketplaces, a major name-brand retailer acquired a popular and successful pioneer in social media. Given the Platform’s uniquely talented and deep bench of software engineers, technologists and user-experience designers, the Buyer made the fateful decision that it would ultimately have to integrate the much smaller and highly entrepreneurial business into its own development team and IT organization eventually anyway, and saw no need to delay this action until accomplishment of key developmental milestones. The results were both predictable and immediate. The high-performance team linkages, Silicon Valley culture and upside growth incentives that attracted the best and brightest talent evaporated as the Buyer’s full absorption model quickly destroyed any semblance of secret sauce the Buyer thought it had acquired.

- Keep the Platform’s sales teams separate, but closely coordinated and incented. A well-known industrial manufacturer was buying its first ever Platform in Europe. In addition to the vastly different regulatory and compliance environment compared to its core North American business, the Platform had pioneered a product utilizing an entirely different raw material, product size and design than the Buyer was accustomed to. These products served a similar end-use as the Buyer’s but within a totally different usage environment, customer preference and direct-to-consumer channels. One more complicating factor: the Buyer had ZERO brand awareness in Europe, compared to a market leading brand of the Platform. As a result, the Buyer wisely determined to carefully co-brand under the Platform’s dominant brand and leave the European sales organization, go-to-market approach and incentives as-is, but with additional Buyer sales support, training and “on-top” incentives for qualified lead pass and cross-sale opportunities.

- Maintain the Platform’s product development, delivery and customer experience without disruption. A product-oriented company bought a significant, new service business that was the clear market leader in its vertical segment and area of service expertise. Over the Platform’s 30-year history, it had meticulously invented and perfected a unique recruiting, selection, training and apprenticing program that enabled the Platform to consistently deliver error-free excellence and top-shelf service in an industry not known for either. During the early stages of integration, the Buyer considered this talent development constraint a threat to its pre-deal growth projections and valuation. Initially, it set out to “supercharge” the Platform’s talent model with its own people, skill set and compensation philosophy. After persistent customer delivery and customer experience fails, the Buyer wisely ditched their approach and instead helped the Platform invest, expand and scale its legacy talent model.

- Let the pace of integration vary in proportion to the overall deal requirements and integration strategy. An old adage in the M&A world is “the best deals wait for no one.” That’s true, but opportunistically timed deals may not always line up well with the Buyer’s readiness to fully support them with core systems, processes or the back-office capabilities needed to scale the Platform to plan. For example, one global software company bought several diverse platform SaaS companies along with select, immediate add-on companies, but took a well-paced, disciplined, long-term approach prior to integrating them all in rapid succession onto a new, but fully featured and vetted SaaS operations platform. Contrast that with a completely different global software company after buying its first-ever, fully mature and at-scale SaaS company in a vertical domain the Buyer had never operated in. Instead of the disciplined approach in the prior example, this Buyer’s global IT organization quickly deployed a fully scalable homegrown SaaS operations platform and rationalized their fast integration logic based on the stack of new deals right behind it. Unfortunately, the Platform company’s operating model, customers, systems, functional requirements, metrics and decision authorities were not fully understood or valued by the Buyer. The Buyer’s resulting internally developed replacement operating platform – while intended to provide global scalability and more robust security and risk management features, far under-delivered the core functionality required merely to sustain the Platform’s base business.

- Help the new Platform get quickly positioned and broadly validated within the Buyer’s organization without slowing their momentum or disrupting their core business. For this one, I want to give full credit where credit is due to my friend, former colleague at M&A Partners and now client, John Christman, who currently serves as Vice President and Head of Global M&A Integration for technology services juggernaut, Cognizant. John’s outstanding prior experience with Dell, and now with Cognizant, really resonates for any Platform acquisition. Accomplishing this important strategy requires direct senior leadership involvement, balance and continual triage of new sales or product innovation opportunities into a “good is an enemy of the best” calculus. Done well, onboarding and positioning a strategically important new Platform is likely to result in so many compelling growth opportunities or “internal gravitational pull” demands that without careful management, you can easily and unintentionally “swamp the boat.”

At the time of writing, Mark Herndon served as President of M&A Partners and was the featured presenter at the M&A Leadership Council's The Art of M&A Integration November 2019. Today, Mark serves as Chairman of the Council. Register to see presentations by Mark and other experts with real-world experience; panel discussions; group exercises; and networking opportunities at upcoming online training sessions.