The Art of M&A® / Negotiating the Letter of Intent and Acquisition Agreement

An excerpt from The Art of M&A, Sixth Edition: A Merger, Acquisition, and Buyout Guide by Alexandra Reed Lajoux

In [the] process of risk allocation, who should bear the risk of loss associated with undisclosed legal defects in the target discovered after the closing—the buyer, the seller, or both? Is there one correct answer?

This is a matter of negotiation. The smart seller will say:

| “Look, before you sign anything, we’ll show you everything we have. Talk to our management, our accountants, and our lawyers. Kick the tires to your heart’s content. If you discover problems, we’ll negotiate a mutually fair resolution in the agreement. Then tell us how much you’ll pay on the assumption that any unknown problems are simply your risk of buying and owning the business. Once we close, the business and the risk are yours.” |

The canny buyer’s answer will be along the following lines:

| “Our contractual arrangements should be structured to provide both of us with strong incentives to unearth problems before the closing. You will have a strong incentive to uncover all the issues only if you share some or all of the risk of undisclosed problems. We’re willing to do our share of tire kicking, but at some point it’s absurd for us to absorb a loss that surfaces notwithstanding our extensive due diligence, a loss that is so large as to make our price far exceed the value of what we acquired. Surely, you don’t want to exact an unfair price under these circumstances.” |

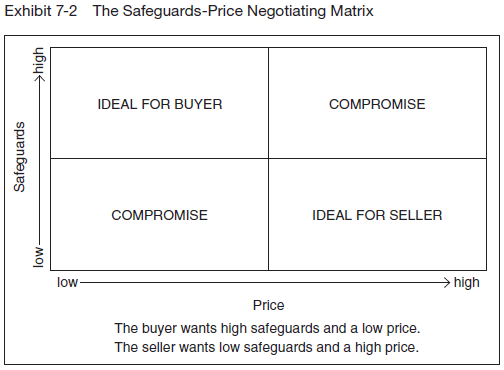

The real issue is: What is a fair price for the target? The answer hinges on the assumptions of the parties when the transaction was negotiated. The buyer can either (1) determine a price based upon assuming the risk, that is, an as-is deal, which presumably would be less than the price that would be paid if the seller retains some or all of the risks; or (2) determine a higher price premised on the seller’s retention of some part of the risk, as shown in Exhibit 7-2.

The first alternative (as-is, low price, low safeguards) may be acceptable to a buyer comfortable with its familiarity with the target, or where the target doesn’t engage in activities that could give rise to extraordinary liabilities (for example, violations of environmental laws or product liabilities). However, it is a gamble.

The second alternative (high price, high safeguards) is much more common. In most sales of private companies, the seller bears a significant portion of the risk of target defects, and the deal is priced accordingly.

This said, however, the seller should not be pestered incessantly about relatively insignificant items that prove not to be true about the target. Everyone knows going into an acquisition that no company is perfect and that in due course blemishes on its legal and financial record will undoubtedly surface. Accordingly, although seller accountability is the general rule, that accountability is usually limited by specifying the time during which it can be held liable and by requiring the buyer to limit its claims to significant problems.

Does the customary practice of making the seller share in post-closing risk—rather than selling as-is—make sense?

Yes, for three reasons:

■ First, an as-is transaction may force the buyer to reduce the purchase price even though the likelihood of a claim is insubstantial.A seller’s concern about postclosing hassles would typically not be serious enough to justify the trade-off in price that might result from forcing a buyer to price the deal on an as-is basis.

■ Second, having the seller share in the risk along with the buyer will provide both buyer and seller with a strong incentive to discover problems before the agreement is signed or the deal is closed. Thorough investigation by both parties that have a stake in the outcome reduces the likelihood that a claim will arise.

■ Third, if the problem were discovered before the closing, it probably would result in a price adjustment, even to an as-is deal. Logically, the result should not be different merely because the problem arises after closing.

This does not mean that every seller should cave in on this issue and agree to take on all the postclosing risk. In certain circumstances, the seller may prefer taking a lower price to avoid the risk of postclosing adversities. Nor should one assume that the pricing will necessarily reflect the risk of an as-is approach. In the case of a deal-hungry buyer, or a buyer that has confidence in its assessment of the risk of loss, the seller may get the best of both worlds—a high price with little or no post-closing risk. This is especially true in a competitive bidding situation. In the end, the allocation of risk will depend more on the bargaining power and negotiating skills of the parties than the niceties of pricing theories.

---------------------------------------------------------

Learn more about mergers, acquisitions and divestitures at M&A Leadership Council's virtual training courses. Network with other M&A professionals while our expert consultant trainers will prepare you for your next transaction (or help with an ongoing one) through sharing practical insights, group discussions, case studies, and breakout exercises.

Lajoux, Alexandra Reed with Capital Expert Services. The Art of M&A, 6th Edition: A Merger, Acquisition, and Buyout Guide. United States of America: McGraw Hill, 2024. Pp. 515-517. Print.